Roadmap To Recovery: When Do the Lost Jobs Return?

A recent __ article cited a survey where 43% of economists saw it taking until 2023 to recover all of the jobs lost to the COVID-19 recession and government response. I tend to generally agree with this sentiment (though exact timing is never easy to predict), so this seemed like a good opportunity to review the macroeconomic picture and layout my long-term thesis in detail.

I’ve written a couple articles for BiggerPockets detailing my thoughts on what’s to come, which is essentially a weak economy with potential deterioration after the Q3 snapback and disinflation or outright deflation in the near- to intermediate-term followed by serious inflation further out. All of this will have a large impact on real estate values and interest rates.

Below I’ll present my argument in greater detail. Hopefully, this will address some of the criticisms I’ve gotten, as well. Then, we’ll talk real estate strategery as it relates to my opinion on where the economy is headed.

Related: __

Economic Weakness on the Horizon

First, let’s cover how and why the economy is expected to be weak for the next several years.

Despite record-low unemployment and encouraging gains in income, the economy in 2019 was showing signs of stress. All ISM Purchasing Measures Index and Fed measures peaked in 2018 and turned down as 2019 progressed. These indicators were in negative territory at the end of 2019 except for employment growth, which was teetering.

It seems the 2019 economy was sending the same signal that my wife sends when she says, “That’s fine. Everything’s fine.”

I’ve been around long enough to read between the lines.

Despite the brilliant minds in Washington implementing various stimulus programs employing a variety of spending increases or tax breaks since the Great Financial Crisis, annual real GDP growth had been relatively modest. The strongest GDP print of the recovery in 2015 barely broke 3%, compared with previous post-war recoveries there were often well over 3% annually, sometimes growing in the 4-5% range.

The 2019 GDP growth of 2.16% was a significant deceleration from the 2.99% growth the prior year. This entire expansion since 2009 underperformed, demonstrated by peak growth far lower than previous expansions.

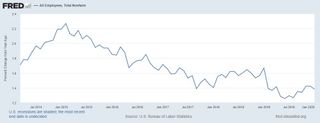

Employment growth had likewise been grinding lower into 2019 after a bump in 2018 due to the tax cuts.

While shorter-term fluctuations in economic growth can be driven by many factors, the long-term economic trajectory of the economy at present is influenced primarily by debt and demographics.

Debt Trap

Research shows that a country’s real GDP growth begins to be impacted when debt to GDP levels exceed 50%, with the negative impact becoming much more severe around 90%. This is explained by the law of diminishing returns.

The more you use something, the less you gain from each additional unit you use. For example, the first Portillo’s Italian beef sandwich I eat gives me great pleasure. The second one I eat is pretty good still, but not great. The third does nothing for me, and by the time I eat my seventh, it is actually making my life worse.

This same effect occurs as an economy gets weighed down by debt. At first, it can have a positive effect on GDP, especially if the debt goes to productive uses that create cash flow to pay back the principal and interest. But after a while it becomes a drag, particularly if the debt goes to consumption and not investment, i.e. borrowing for a car vs. borrowing to buy an investment property.

Due to the low interest rate policy of the Federal Reserve and the fiscal policy of the U.S. government, we’ve seen a large increase in both government and private sector debt. This debt overhang will weigh on GDP growth over time, notwithstanding any transitory boosts due to “stimulus” programs, tax cuts, or other short-term events.

As shown below by decade, the addition of more debt leads to weaker GDP growth over time.

With Q2 2020 debt to nominal GDP spiking to 135%, we can expect sluggish long-term GDP growth and a low-inflation or even deflationary environment going forward. Any boosts from government intervention are likely to be transitory.

The increased debt will serve to crowd out the private sector and allocate economic resources to less productive uses, contributing to weaker economic growth.

Shown below, as debt load increases, each additional dollar of debt generates less GDP. In the 2010s, only about 34 cents of GDP were created for each additional dollar of federal debt.

Corporate Sector

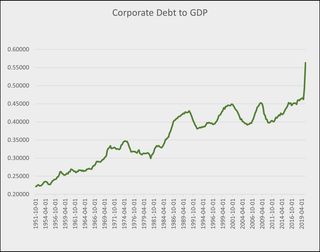

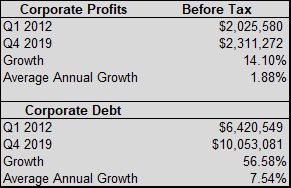

The corporate sector had been showing signs of strain leading into the pandemic. Corporate debt to GDP has reached the highest levels in history, while profitability has waned. Before exploding higher due to the pandemic, corporations were already at levels consistent with impending recessions.

Corporate profits from Q1 2012 to Q4 2019 increased at approximately 1.9% per year, while debt grew at 7.5%. This differential in growth rates is unsustainable and only allowed by increasingly low borrowing costs.

The overall result is a debt-dependent economy, which had continued to add leverage while profitability did not keep up.

This over-leveraged position exacerbated the potential losses from a recession and left the corporate sector vulnerable to a disruption in cash flow.

While many larger companies were able to avoid bankruptcy, their higher-leverage positions signal that they are not yet out of the woods and may require further assistance in the future.

Creative Destruction and Moral Hazard

Profits and losses are a vital feature of properly functioning economies. They serve as a signal for where to direct capital and resources to alleviate shortages or surpluses.

When a firm is unable to meet the needs of the economy, it may go bankrupt. While this causes short-term pain, the resources previously employed by the firm can now be reallocated to other areas where they are needed.

This process allows for higher productivity over time as the resources in the economy are allocated to their most efficient uses. Economist Joseph Schumpeter called this process “creative destruction.”

One of the unintended consequences of the intervention of the Federal Reserve and various regulatory bodies has been to impede the process of creative destruction. By providing artificially low interest rates, guaranteed loans, and sometimes outright direct financial assistance, there have been many firms since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 that have avoided bankruptcy.

_ Related: _

While this obviously benefits the employees and management teams of these firms, it also results in resources being “trapped” in firms that would otherwise not exist. These resources cannot therefore be employed in more productive uses that would suit the needs of the economy better.

Companies that remain afloat due to their ability to borrow at low rates, and whose debt costs are larger than profits, are sometimes referred to as “zombie” companies.

The repeated bailouts and easy money policies have also created moral hazard. Businesses take greater risks when there is a perceived backstop from the government. This leads to higher debt loads and more aggressive expansions, which create larger potential losses if the economy turns.

Impeding creative destructive and creating moral hazard also puts long-term strain on the economy and increases the likelihood of weaker long-term growth.

Adding private debt to the picture shows the massive disconnect between systemic leverage and the underlying economy. Since borrowing money is simply pulling future spending forward, the ability to service this debt load will weigh on GDP growth over the long term.

Demographic Headwinds

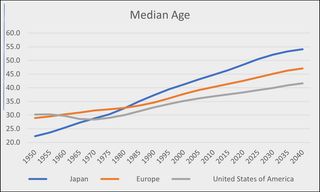

Demographic trends in the U.S. provide additional ammunition for the slow growth, low-inflation thesis. As the country ages, consumption tends to slow, and an increasing proportion of the population shifts toward retirement while claiming Social Security and Medicare benefits.

As the Eurozone and Japan have demonstrated, the tendency will be toward continued debt growth and weak economic output. Japan, with the oldest population and highest debt, tends to grow at the slowest pace, followed by Europe, and then the U.S., which has the youngest population but is approaching an inflection point with the Boomer generation retiring.

Inflation has not materialized in Japan or the Eurozone despite massive “money creation” and is unlikely to materialize in the United States absent a change in the restrictions of the Federal Reserve (discussed later).

Given the current situation, getting back all of the lost jobs is likely to be a long slog. It is unlikely to see employment at pre-recession levels for a few years given the long-term headwinds facing the economy.

Looking at the GDP decline by state we can see that across the country—with no exceptions—we are looking at a large drawdown in economic activity that will take time to recover from. This is likely to add to the debt burden over time.

The constant drag of over-indebtedness combined with an aging population is a recipe for weak GDP growth in the coming years.

The economy is an old marathon runner with a belly full of seven Italian beefs. With hot giardiniera and mozzarella cheese. I’ll be right back—heading to Portillo’s.

Inflation and Monetary Policy

The Federal Reserve cannot, on its own, create inflation.

When the Fed buys Treasury bonds, they create base money out of thin air. However, this is created in the form of bank reserves, which are held at the Fed and can not be removed. They are not legal tender and do not make their way directly into the real economy.

Quantitative easing (QE) can be more accurately understood as a swap, whereby the Fed replaces interest-bearing Treasuries with non-interest-bearing reserves held at the Fed.

Banks can, however, lend against these reserves. To do so, they must be willing to risk their capital and earn a premium sufficient to cover their costs plus a profit. They must also find a borrower willing to risk their collateral in order to expand and grow their business.

Given the preceding commentary pointing to slow growth, and the large output gap currently in place due to the COVID -19 recession, massive bank lending large enough to generate inflation is unlikely. Disinflation or deflation is the larger threat over the next few years given the increase in unemployed workers and the number of businesses that have shut down.

Interest rates should reflect this reality and continue to head down over the intermediate-term.

So, Why Am I Calling for Inflation?

Because the writing is on the wall. In the long run, there is absolutely no way that the federal government can repay its debts. The only possible solutions are to slash spending, raise taxes DRASTICALLY, or to inflate away the debt.

Raise your hand if you think a politician will cut spending or raise taxes massively on the middle class. Anyone? Bueller?

Think of bank reserves, Treasury bonds, and dollars all as government liabilities. Some have different restrictions or pay interest, but they’re all issued and owed by the government. Currently, the preferred method of financing deficits is to issue Treasuries, some of which the Fed then converts to bank reserves through QE.

Whatever form they take, these liabilities must exist and be held in some form until they are retired. As Congress continues to create Treasury bonds at an unsustainable pace, the Federal Reserve will do everything they can to continue purchasing them so that interest rates remain low.

Can they continually be “trapped” in the banking system as reserves and keep inflation at bay? Short term, yes. Long term, I’m not so sure.

I think that several years down the road, after several years of trillion-dollar deficits, when global markets become more interested in solvency than liquidity and the economy and employment are growing, a general revulsion toward holding these liabilities will occur. Markets will prefer to hold their wealth in commodities or convert it to consumption, and 1970s-style inflation will pick up.

MMT: The Game Changer

Modern monetary theory (MMT) is gaining steam in mainstream discussions. The extremely short explanation of MMT is that it’s not really modern and not much of a theory. The idea is that the government can and should create legal tender out of thin air, spend it in the economy to achieve whatever goal it thinks it can achieve, and tax it out of the economy if inflation becomes a problem. What could possibly go wrong?

Should the government change the rules and allow the Fed to directly credit people’s accounts with spendable cash, the inflation picture changes completely. This would be true money creation and brings with it the risk of going from the 1970s-style inflation I described above to Zimbabwe-style hyperinflation.

Regardless of whether or not you think it’s a good idea, monitoring these developments is critical and the impact on the entire investing world is immense.

Real Estate Is the Place To Be

All roads lead back to real estate investing, especially multifamily and storage.

Over the short term, if we do have economic troubles and deleveraging, we will see better deals emerge and the weaker players will get shaken out. People will always need a place to live and keep their stuff. In an environment where bonds yield nothing and stocks are priced to perfection, real estate returns look great.

When inflation does come our way down the road, hard tangible assets will perform the best. They aren’t making any more land and the value expressed in terms of government liabilities has a good chance of growing at a similar or better pace compared to goods and services.

You’ve also got the added benefit of paying future debt service with increasingly devalued dollars, thereby benefitting from inflation in the same way the government is set to benefit.

Good luck out there!

What are your predictions for the economy over the next few years?

Tell us your vision in the comments.